Eugene's Amazing Summer of Art

For a brief moment in 1974, Eugene turned itself into a powerhouse of big public sculpture

In yesterday’s Eugene Weekly I have a short piece about the 1974 Oregon International Sculpture Symposium, an event that for one brief shining moment put Eugene on the art world map as six well known sculptors came to town and worked in public for six weeks.

Several readers have asked me for more information about the symposium. Here’s a story I did for The Register-Guard in 2004 on the 30th anniversary of that summer of art. I’ve gone through and updated some of the information and date references from the original published version so it makes more sense in 2024.

Next to the Willamette River in Eugene’s Alton Baker Park, seven whimsical figures cavort in a mysterious group, like space aliens frozen flat in concrete. You may have seen them near the Ferry Street Bridge, a cross between Alice in Wonderland and Stonehenge, their cast forms nicely weathered with age.

Most people around here know them. And most people have no idea that they grew out of the biggest visual art event this town has ever seen.

Fifty years ago this summer, six world-class sculptors came to Eugene, where they worked for six weeks in public — some in Alton Baker Park, others at Lane Community College — to create monumental art works for the Oregon International Sculpture Symposium.

For one brief moment that summer of 1974, Eugene found itself located clearly on the world’s art map. Nothing like the symposium had ever happened here before. Nothing like it has happened here since — nor is it likely to, in the near future anyway.

”There was a huge burst of energy that was happening in Eugene right about that time,” said Eugene lawyer and art expert Roger Saydack. “The commitment people were willing to make to permanent artistic statements was amazing. It took a lot of daring. The two art forms you almost never see in smaller cities are monumental sculpture and opera. And we have both here.”

The symposium grew from an unlikely combination of money — Eugene was awash in timber dollars in those days, feeding the coffers of public arts budgets — and the vision of a persistent artist, Jan Zach, and a persistent arts patron, Hope Pressman.

An internationally known sculptor when he arrived at the University of Oregon in 1958, Zach sounded out artists as early as 1964 about the idea of a summer symposium here. Encouraged by their response, he and Pressman finally pulled together a $145,000 budget, with the help of a $45,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and brought the six sculptors to town.

Zach, who died in 1986, was an unstoppable force. “He was very difficult to say ‘no’ to,” recalled Pressman, who was the symposium’s executive director. “He was a pest. He drove everybody incredibly hard.”

Four of the artists created large works that can still be seen here three decades later, giving the community a substantial legacy of public art.

The symposium also left Eugene with a vision of itself as an art town, a notion that persists today. “We've got really fine works of art placed around town that people enjoyed seeing made,” Pressman said. “And the exposure to the way art is made had a great effect on a lot of people.”

Hard for some to like

The best-known symposium sculpture may be “Big Red,” which sits at the entrance to the Washington-Jefferson Street Bridge, looking like a giant steel dumbbell. Another is the space aliens by the river. A third piece, also in Alton Baker Park, looks at first glance like a giant piece of rusty industrial debris that fell from the sky.

A fourth work is the large basalt forms at the Lane County Public Services Building. Work by a fifth artist went to Mount Hood Community College, where it’s still on display; and the fragile sculpture done by the sixth artist — the man who was the most famous of the lot — was damaged and has disappeared.

Almost completely nonrepresentational, the art made here that summer is hard for a lot of people to like. None of the pieces looks like anything, nor are they meant to. They’re modern, stark, aloof, industrial and spare, just as their creators intended them to be, a snapshot of art in the late 20th century. This wasn’t a group of artists given to sculpting scenic wildlife or heroic pioneers.

For sculptor Dimitri Hadzi, who would go on from Eugene to teach sculpture the following year at Harvard University, the symposium was a life-changing event. The artist, who worked in those days in New York and Rome, took seriously Zach’s two unusual conditions for coming to Eugene: The artists were to work with an unfamiliar medium and they were to work in public.

Hadzi, who had sculpted before primarily in bronze, came to Oregon early to explore native materials. He first thought of wood, this being a timber state, but was drawn to the vast expanses he saw of dark volcanic basalt.

“Few people work in it,” he said in a telephone interview from his studio in Cambridge, Mass. “It’s a tough material, not very friendly. I loved it: the color, the fine polish you get on it. The whole mystery of getting a block to work.”

Though he wasn’t certain he liked the idea at first, Hadzi also worked in public, setting up his sculpture studio in the park and working through the day and, under lights, into the night. Not only did he have people watching, he had assistants to deal with.

“I am a loner,” he said. “Or used to be a loner. I never had any help. Suddenly, I was confronted with 10 to 15 people helping me at a time. When you're working alone, your mind floats around and you arrive at solutions, eventually. When you work with a group like that, you have to make snap decisions and you have to make good ones.”

The year after he was in Eugene, Hadzi was offered a job teaching sculpture and print-making at Harvard. It was the only teaching job he accepted in his career; he took it, to some degree, because of his enjoyment of teaching here, Hadzi said.

“It’s the only experience like it I've ever had,” Hadzi said of the symposium. "I have never heard of any other thing like it.”

The party artist

The charming bad boy of the symposium was pop artist John Chamberlain, the only one of the six with his own listing in the Oxford Dictionary of Art. An associate of Andy Warhol’s known in the 1970s for abstract art made of crushed car bodies, Chamberlain drank and partied his way through much of that summer of ’74.

“Eugene? I don’t remember it,” said Chamberlain 30 years after the event. “Sort of, I guess. I think I liked it because I got out of New York and could breathe fresh air and ride my bike. But I drank my share and your share and a few other people’s share while I was there.”

For his formal symposium lecture in the Eugene City Council chambers, Chamberlain showed a 69-minute film, “The Secret Life of Hernando Cortez,” that he’d directed in 1968 in the Yucatan with Taylor Mead as Cortez and Ultra Violet as a courtesan.

Described in a New York film festival brochure as “so pointless and silly it’s actually quite endearing,” the movie, with its nudity, caused a Eugene council member to call police, who showed up at City Hall but refused to shut the screening down.

For his sculpture, Chamberlain wanted to build a huge tower of crushed car bodies next to the Lane County Public Service Building then being planned for downtown.

“I proposed a cubic acre of crushed cars,” Chamberlain said. “Using the cars as bricks. That never happened. A couple guys and I sat around getting drunk once and figured out it takes 400,000 cars to make a cubic acre. I’ve proposed a whole bunch of stuff that nobody is ever going to do.”

Lane County turned him down — the county building ended up getting Hadzi’s basalt monoliths instead — and Chamberlain set to work on a 10-foot foil bag that looked like a giant crumpled candy wrapper. He worked the metal sheets by hand, climbed inside the bag and punched it into shape, and finally rammed it from the outside with a Volkswagen. The piece was as much performance art as sculpture.

It’s the only piece from the symposium that's gone missing. It's not in the collection of the Schnitzer Museum of Art at the university, as some accounts suggest. One story is that a UO art faculty member borrowed it years ago, but she was out of town when I called and couldn't be reached for comment, so the mystery remained. Chamberlain himself dimly recalled that “some guy from Portland” took it away after the symposium.

Rejected by Bend

The creator of the riverside space aliens, Hugh Townley, was charmed by Eugene’s easy-going attitude. He recalls looking for something to do here on the Fourth of July.

“We drove down next to the Willamette River on a picnic,” said Townley, who was living in Vermont when we talked. “And in the course of that drive, we passed people swimming nude in the river, people throwing bottles in the river and shooting at them, and people obviously smoking copious quantities of pot. We were driving two cars behind a state trooper, and yet it all seemed to be all right. I thought this was a nice indication of the integration of all these things into the local society without anybody being annoyed by it.”

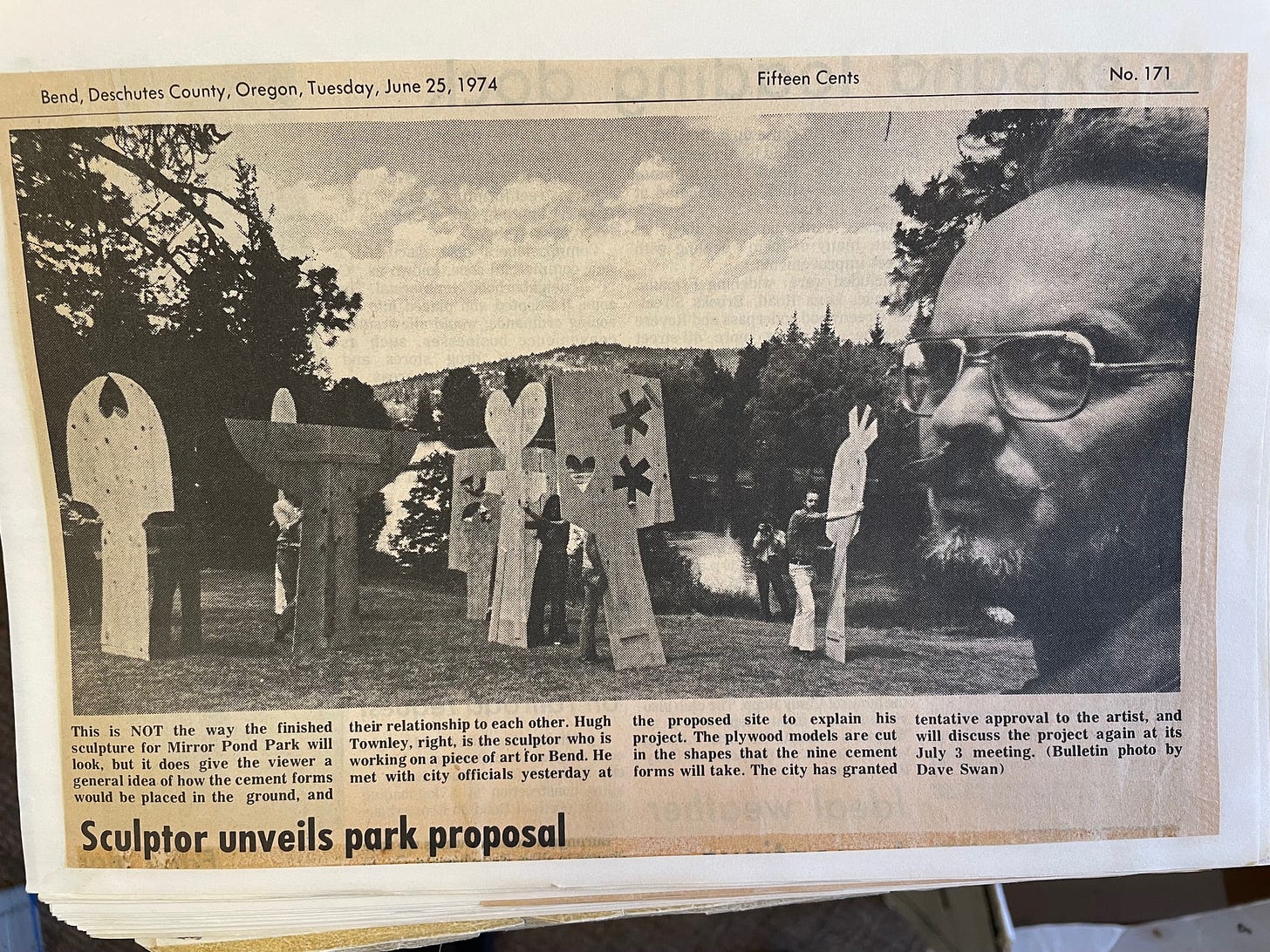

The artist originally proposed his quirky statues for the city of Bend, which was going to place them in Drake Mirror Pond park — right up to the day Townley and his assistants showed up in Bend with plywood mock-ups of the work.

“A photographer at the newspaper did a good job, a wonderful wide-angle photographic shot of me that was quite grotesque and circuslike,” Townley said. “After seeing that on the front page, nobody would want the damned thing out there.”

Bend officials turned the art down after hundreds of residents signed petitions saying the proposed art was ugly and misplaced. “They didn't want anything to do with it,” Townley said. "If we wanted a piece of sculpture in there, it would have to be a wagon wheel or a horse. It was a wonderful reaction! What could you do? If you can't roll with the punches with a commission like that, you're in deep trouble.”

After a quick scramble, it found a home at Alton Baker Park. “I am very happy with the sculpture where it is,” he said.

Not far from the Townley piece in the park is something that looks a lot like rusty steel panels radiating from a 10-foot central post. In fact, the panels used to rotate like hinges on the post, though they don’t anymore.

Tony Rosenthal, the New York sculptor who designed it, apologized in our interview about its shortcomings. First off, Rosenthal, 90 years old and and living in Southampton, N.Y., when we talked, didn’t actually show up for much of the symposium, to the irritation of some of the other artists. He had, he said, a large commission he was completing in New York at the time and had to leave Eugene in the middle of the summer.

And because of his absence, he said, the Eugene sculpture was poorly constructed: “The piece I made, on the little model, the large pieces moved. And if I had been there when they put it together, they would have understood you had to put in a separator or a washer on the parts of the sleeve that went over the pipe.”

A famous Rosenthal piece that still moves correctly has become a Manhattan landmark since it was installed in 1966 at the corner of Astor Place and Eighth Street. Though it’s formally titled “Alamo,” most people call it simply “the Cube.” The metal cube, 9 feet on a side, is poised on one corner and can be rotated with a firm shove.

Strong connections

Now 85 years old, sculptor Bruce Beasley, creator of “Big Red,” is the only one of that summer’s artists still alive. He has maintained his connections with Eugene for years. The Oakland, Calif., artist traveled here to install a new, smaller sculpture in front of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. He regarded that summer of the symposium as a key time in his life.

”I feel very close to Eugene,” he said. “It was a wonderful time. It was a very lovely summer, very hard work, very intense, a wonderful feeling. The community involvement was rich and robust. And I love where my piece ended up!”

The symposium left its mark in other ways, too.

Legal work for the symposium was done by a young lawyer named John Frohnmayer, fresh out of law school at the UO.

Frohnmayer, the brother of former UO President Dave Frohnmayer, had never thought too much about art law before joining the symposium’s board of directors. He learned fast. One challenge was getting insurance, which he managed to do just in time before an artist turned over a rented boom truck in the park, fortunately without any injuries.

Years later, Frohnmayer became chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, a job he held from 1989 until he was fired by then-President George H.W. Bush in 1992.

”The symposium was really the start of my career in public art,” he said. “I found out how much fun artists were. Just hanging around those people and listening to the ideas that motivated them was something I appreciated very much.”

But Frohnmayer said the symposium had far greater significance for the community and worried that the kind of energy he saw in Eugene that summer hasn't returned.

”It was an extraordinary event, one that has significance for generations of Oregonians,” he said. “Are we leaving that kind of a legacy for future generations today? I think, for the most part, the answer is ‘no.’”

THE WORK

Bruce Beasley (1939- ): “Big Red,” the bright red metal sculpture in Washington Jefferson Park.

Roger Bolomey (1918-2011): Vertical wood structures near the theater at Mount Hood Community College outside Portland.

John Chamberlain (1927-2011): A 10-foot foil-and-resin bag, now disappeared.

Dimitri Hadzi (1921-2006): The basalt monoliths on the first floor terrace at the Lane County Public Service Building; also basalt pieces in Alton Baker Park near the picnic shelter.

Tony Rosenthal(1914-2009): The 10-foot-tall oxidized steel piece in Alton Baker Park.

Hugh Townley (1923-2008): The seven abstract figures next to the Willamette River in Alton Baker Park.

I remember a time when Eugene had so many art galleries that a First Friday Art Walk could be focused within a few blocks of the downtown core. It was an interesting time that seems to have disappeared with the great recession and later Covid. I wonder if Eugene will ever become a center for the arts here in mid-Oregon again.