A deeper loss that follows the death of newspapers

Where is the next great American novel going to be born now that newsrooms are dying? Surely not in an MFA program somewhere.

As newspapers around the country continue to collapse from the metastasizing cancer of the web and social media, pundits warn us almost daily about the end of democracy when all those newsrooms are gone.

Yes, newspapers provide a much-needed watchdog for government. The problem isn’t just about democracy, though.

No one seems to have noticed a huge loss that looms as the newspaper business heads for hospice care. For more than a century, newspapers of all kinds and sizes have served as an incubator for good literature.

The hothouse atmosphere of newsrooms, especially at urban dailies, teaches the aspiring writer more about the world, about life, and about writing than any MFA program ever devised. And when the aspiring novelist, poet or screenwriter moves on from newspaper work — if they ever do break free of the addiction — they don’t pick up crippling financial debt along with their diploma.

Who are we talking about here? Think Mark Twain. Ernest Hemingway. Think James M. Cain, the author of two brilliant Depression-era novels, The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity. Cain learned the writing business in the newsrooms of the Baltimore American and later the Baltimore Sun, where he worked under H.L. Mencken.

His brisk, unornamented prose defined the noir genre of fiction and paved the way for Hemingway’s concise literary realism.

Here’s what Tom Wolfe, another journalist turned novelist, wrote about Cain in 1969:

Cain was one of those writers who first amazed me and delighted me when I was old enough to start looking around and seeing what was being done in American literature… I can see how complex Cain’s famous ‘fast-paced,’ ‘hard-boiled’ technique really is.

The list of newsroom alums goes on. Charles Dickens. Thomas Thompson. Ken Follett. Michael Connelly, the L.A. Times cop reporter who created the marvelous series on the fictional detective Hieronymus Bosch. Hunter S. Thompson. Raymond Chandler. Tony Hillerman. Charles Portis. Thomas Harris. Carl Hiaasen. Margaret Mitchell, who wrote for The Atlanta Journal a decade before Gone With the Wind was published.

And there are poets, such as Maya Angelou and Walt Whitman, whom you’ve probably heard of, and others whose reputations have faded over the years, such as Joaquin Miller, the nationally known 19th century writer who dubbed himself the “Poet of the Sierras.” Miller, for you Eugene readers, was for several months in 1862 an editor at the Eugene Democratic Register, or Democratic Herald, depending on which version of the name you prefer.

This isn’t solely an American phenomenon. Bram Stoker wrote for the Dublin Evening Mail before turning his attention to Dracula. H.G. Wells wrote for the Pall Mall Gazette in London before he wrote The Time Machine. Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote for El Universal, then El Heraldo and El Espectador in Colombia before his novel One Hundred Years of Solitude was published in 1967.

Working in a newsroom teaches an array of skills necessary for literary writing. Besides exposing the would-be novelist or poet to a vast spectrum of characters in real life, the job teaches the discipline of writing fast and clear while distilling a tale to its essence. It ultimately shapes a deep understanding of stories and story structure.

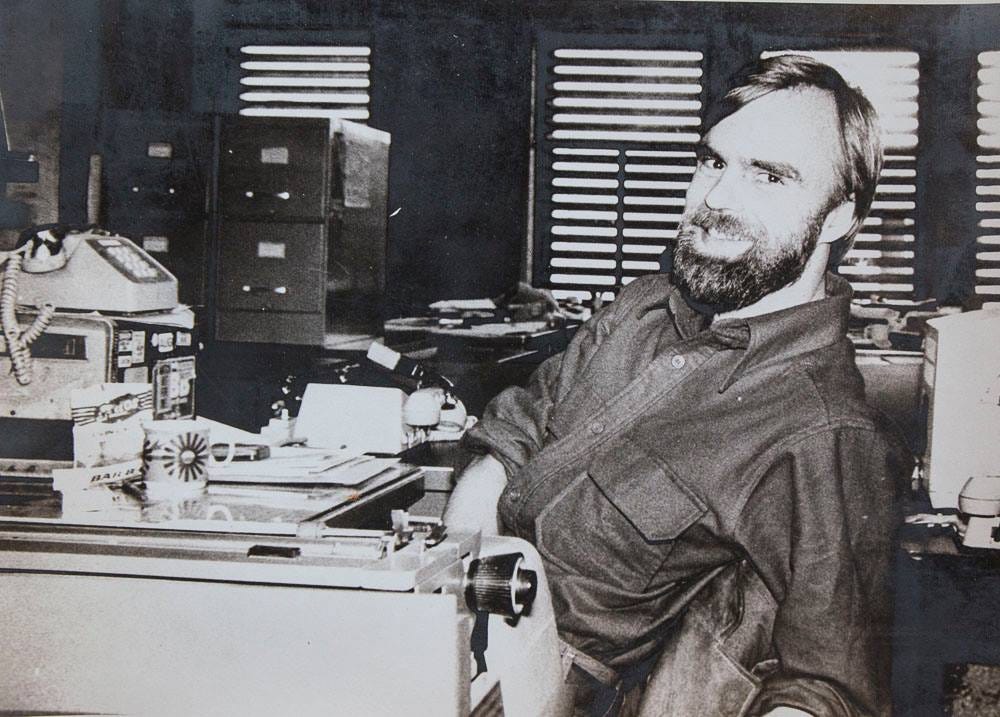

One of the most helpful editors of my career was a man named Lou Godfrey, the night assistant city editor at the Long Beach Press-Telegram in 1977, when I was inexplicably hired there as the night cop reporter despite my utter lack of daily newspaper experience or training.

Late at night Lou would toss me a photo of a fatal traffic accident or crime scene, clipped to a copy of a police report, and tell me to write a caption for the morning street edition that accurately explained what happened, all with active, interesting verbs and without police jargon, and running for no more than three lines of printed text. I would draft something as quickly as I could, turn it in, and listen with dread as Lou dismissed it as “too soft,” “too boring,” “not enough facts here,” or “probably libelous” and throw back it at me. “You’ve got five more minutes,” he’d add.

That kind of stress was nothing compared to dictating breaking news stories on a two-way radio live from the scene. This was well before cell phones and texting. I’d be sent out on a late-night shooting, or traffic accident, or fire, and be expected to file my story by talking into an awkward walkie-talkie that looked like something an infantry radio man might have carried into battle in Korea. I’d get on the radio with Lou, or one of the more-senior reporters, and tell my story out loud with minutes to go before the final deadline for front page news.

Fortunately I was put on the receiving end of such conversations enough times that I knew the drill before I had to do it myself. You talk slowly and clearly, enunciating each word and spelling anything difficult, especially names, while putting the punctuation into words: “Police identified the driver as 45 hyphen year hyphen old Jaymes J A Y M E S Centurion C E N T U R I O N of Lakewood period, new paragraph.”

Deadline writing demands simplicity, brevity and clarity. There is no margin for error, and no room for writer’s block. And it taught me to start assembling the story in my head from the moment I arrived at the scene or asked the first question in the first interview.

If the reporter radioing from the field froze or got confused, it was the job of the person taking the call to break the jam. “Look around,” they might say. “How many people are watching this fire? How many fire trucks do you see? Can you still see flames? How high? Is there smoke? What’s the air smell like? Any rescues? Anybody being put into an ambulance?”

Story telling is, at its root, an oral tradition, and learning to dictate a story off the top of my head made me a vastly better — and faster — writer than I had ever been before I had a police press pass.

No, I didn’t grow up to be a great American novelist. But I have written a few novels, and I self-published one on Amazon a few years ago. Idaho: A (dark) love story is a contemporary noir tale set in the Northwest’s art world, and yes, you can buy it right here.

Newspaper work has also launched careers for other forms of writing. Peter Schjeldahl, the late art critic at The New Yorker, wrote this about his experience as a beginner at a newspaper in New Jersey:

I acquired the most useful writing discipline of my life from fat, cigar-chewing Jersey Journal copy editors — burned-out reporters — at desks in a half circle facing the city editor. With No. 1 pencils, like black crayons, they’d eviscerate my copy. I’d rewrite, and they’d do it again. Finally, they sent it down to the Linotype — the old racketing, reeking contraption for setting type from molten lead. Those men still sit by as I write, pencils in their itching paws.

They didn’t use Linotypes in Long Beach, though they did at the tiny twice-weekly I worked at in the San Joaquin Valley right out of college. And I completely recognize Schjeldahl’s description of the burned-out but sharply intelligent old men who populated the night copy desk at the Press-Telegram, easing their job with erudite wisecracks fueled by whisky kept in desk drawers and by lunch breaks at the Press Club Bar across Pine Avenue from the newsroom.

John Steinbeck once said of journalism, “It is the mother of literature and the perpetrator of crap.” OK, even the best mothers have their flaws. But actually being paid money to write stories each week beats the hell out of getting yourself $100,000 in debt in a creative writing MFA program. And you learn a lot more.

Yes, you may make a few useful professional contacts if you get accepted to the right school for that MFA. But if you work in a newsroom in a city of any size, you can make those contacts on your own. I knew a guy in L.A. who wanted to become a screenwriter. He couldn’t afford film school, so he got himself a job as a copy boy at the Hearst-owned L.A. Herald-Examiner, which in my youth was the other big paper in Southern California after the Times. He worked hard, pestered editors with good story ideas, and was soon moved up into an entertainment writing job — covering Hollywood. Within a couple years he was on a first-name basis with many of the people he needed to know in the film business, and within a couple more years he got an agent, quit the paper and started getting paid for screenplays. All this without a penny of student debt.

So as I watch the steady death toll of newspapers in the U.S., I wonder: Where will the next crop of young writers find such an inexpensive and useful education in this arid world of TikTok and AI-produced multimedia?

My parents subscribed to the LA Times, the NYT, and the Santa Barbara News Press, which long ago was a very good local paper. Dad was a newspaper photographer in his young days and spoke into his 90s about his mentors there. I subscribe to the RG because I can’t quite stand to have the lights go out.

You worked hard on this piece-I appreciate that even enough it isn’t my story. Journalism was a predominantly white guy club that I was unable to break into. But that is important history to remember as we morph into something very very different